Cinema-Scene.com

Volume 3, Number 52

This Week's Reviews: The Royal Tenenbaums, In the Bedroom,

Ali.

This Week's Omissions: NONE.

|

The Royal Tenenbaums

(Dir: Wes Anderson, Starring Gene Hackman,

Anjelica Huston, Ben Stiller, Gwyneth Paltrow, Luke Wilson, Owen Wilson, Danny Glover,

Kumar Pallana, Bill Murray, Seymour Cassel, Grant Rosenmeyer, Jonah Meyerson, Stephen Lea

Sheppard, Larry Pine, and Alec Baldwin)

more

BY: DAVID PERRY |

"If you really want to know about me, the first thing

you'll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like,

and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David

Copperfield kind of crap, but I don't feel like going into it."

For a film so reminiscent of the writings of J.D. Salinger,

with highly intellectual youths living unhappy lives because of their often insufficient

parenting, it is surprising that Wes Anderson's The Royal Tenenbaums is not a

highly depressing work like Salinger's Catcher in the Rye (which starts off with

those words) and Nine Stories.

But Anderson and his co-writer Owen Wilson are interested

in something that Salinger probably didn't care about -- they infuse so much compassion

into their storytelling that the milieu of their characters are both heart-breaking and

funny. People have already accused The Royal Tenenbaums of being a failed attempt

at Salinger, but it is simply a revitalization of Salinger's ideas, not necessarily his

style. The Anderson-Wilson team, best known for their work together on Rushmore

three years ago, have a sense of humor more akin to Preston Sturges, who looked

affectionately on his quirky characters.

The Tenenbaum kids have grown up in a melancholy world of

intelligence and luxury. Their father Royal (Hackman) spent their early years brining

money to the family as a great New York lawyer; their mother Etheline (Huston), meanwhile,

made them pursue knowledge and skills in their formative years. From this, they created a

financial whiz in Chas (Stiller), an award-winning playwright in Margot (Paltrow), and an

incredible tennis player in Richie (Luke Wilson).

However, all is not well in the Tenenbaum household --

Royal may be a great bread-bearer, but his abilities in patriarchal actions is rather

lacking. He stole money from Chas' safety deposit box and always reminded Margot that she

was adopted; only Richie was invited to his father-child outings, which usually involved

gambling and other assorted misdemeanors.

Now, after Royal has been absent from the family for 22

years (Etheline finally threw him out), he feels a need to get back into their good

graces. Perhaps it's that he has heartened over time, perhaps it's that he wants to

finally meet his grandchildren, perhaps it's that Etheline is now being courted by her

longtime accountant Henry Sherman (Glover), or, most likely, it's that he is out of money

and needs a place to stay. Conspiring with family butler and faithful friend Pagoda (Kumar

Pallana), Royal convinces Etheline and the kids, now all depressed adults without any

grasp of the exuberance they lost because of their father, that he has stomach cancer with

a prognosis of only six weeks left.

Nearly every facet of The Royal Tenenbaums' story

is that of a depressing nature, but the filmmakers are so keen on the sublime quirks of

their characters that the movie turns into one of the funniest films of the year. Even

when Royal is saying and doing some of the most horrid things a father can utter to his

children, the fine writing and acting by Hackman turns the scene into a laughing matter

instead of a scene caught from a John Irving novel.

Part of the reason Anderson is able to get away with this

is that The Royal Tenenbaums feels far more like a fictional story than either of

his previous films, Bottle Rocket and Rushmore. The geography -- there

are many references to the 375th street YMCA -- and look of Anderson's New York is like a

fairytale. Some have attacked Jean-Pierre Jeunet for his idealized Paris in Amélie,

but failed to notice that Anderson is just as quick to film New York devoid of any

realistic qualities.

In a Fresh Air interview for National Public

Radio, Anderson noted that he tried to make the exteriors feel like 1970's New York while

the interiors were like the 1930's. In doing this, he creates a paradoxical -- and,

without a doubt, novel -- setting for his film. Where we are accosted with J.D. Salinger

outside, F. Scott Fitzgerald seems to be waiting inside. For the audience, the children's

need to return home in the first act of the film seems completely understandable

considering the lousy worlds they have entered since leaving the Tenenbaum home.

The characterizations are uncanny. Paltrow and Stiller get

free rein to go crazy in their characters, which means that Chas is about to jump out of

his body in excitement and Margot looks like she needs to go pout from despair. Luke

Wilson pulls a Bjorn Borg, Owen Wilson a Cormac McCarthy (as Richie's childhood friend,

now a best-selling novelist), and Bill Murray an Oliver Saks (as Margot's neurologist

husband). All the while, Gene Hackman gives the best performance in his later career. At

one point, he is seen riding a go-cart with his grandchildren with total happiness -- the

scene is filmed in almost the exact same fashion as Hackman's famous car chase in The

French Connection (one of the films Anderson based his exterior 1970's New York on)

but with a positive bend.

Comparison is something that The Royal Tenenbaums

was born into. The film has so many literary precursors that they read like a library

checkout list from the adult section, probably one that Margot may have had when she was

six. However, the real comparison that will haunt The Royal Tenenbaums is to

Anderson's previous outing Rushmore. I personally got more out of the effective

joyousness of Rushmore than the underlying sadness of The Royal Tenenbaums,

but I respect both films on the same playing field. Where Anderson has grown as a

filmmaker and a storyteller (there's no questioning that he is more in-tune with his

screenplay here than in his other films), he has lost some of that young optimism that was

so alive in Bottle Rocket and Rushmore. He has grown into a Tenenbaum

for this film, and the transformation is both exultant and depressing. Margot would

probably love to write a play about it.

BUY THIS FILM'S

FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM

|

|

In the Bedroom

(Dir: Todd Field, Starring Tom Wilkinson, Sissy

Spacek, Nick Stahl, Marisa Tomei, William Mapother, William Wise, Celia Weston, Karen

Allen, Frank T. Wells, W. Clapham Murray, Justin Ashforth, and Terry A. Burgess)

more

BY: DAVID PERRY |

Before I begin writing about this film, I want to stop

anyone who is reading this review without having seen the film. In the Bedroom,

with its sudden change of pace at the end of the first act, deserves to retain the

surprise that comes with it. Also, it is nearly impossible to write about the themes in

the film without going beyond that moment. Stop reading now if you have not seen the film.

Todd Field's directorial debut packs more emotional wallop

than any other American film this year. It's closest relatives -- Affliction, Exotica,

The Sweet Hereafter -- all have been seen as deep films without anything outside

of visceral stimulation. Todd Field poses the retort to that assumption: so what?

It is rare to find filmmakers so sure of their art that

they will show restraint and allow the stories to be the show. I have long written on my

distaste for directors like Guy Ritchie and Michael Bay, who use style as the only toy at

their disposal. Todd Field instead shows that the scenarios can create a far more exciting

movie than one surrounding its multitudinous edits.

In the Bedroom was the biggest film to come out of

the Sundance Film Festival this year. With its dual acting awards and a collection of

supporters in almost all professions at the festival, the movie became a

wait-'til-you-see-this release that critics from film festivals love to speak of. Their

adulation is deserved; not only is In the Bedroom one of the best independent

films this year, it is also one of the finest films released this year, independent,

foreign, or studio.

The movie is about pain and anguish, the way a family can

suffer in the face of insurmountable loss. The protagonists are Matt (Wilkinson) and Ruth

Fowler (Spacek), but they are far from heroes; the Fowler's are just realistic people

living through something that happens all the time in the world. When their son Frank

(Stahl) is killed, they must try to find reasoning for their lives to continue. This is an

adult drama dealing with adult issues -- the pain that is present in this film is far from

cathartic for the audience, we too are taken into the anguish that these two are feeling.

Suffering was a major issue in The Sweet Hereafter,

another film about parents dealing with losing their children. The Fowler's, however,

stray from the parents of The Sweet Hereafter: they have someone to blame since

their son was senselessly killed by the separated husband of Frank's girlfriend (Tomei). I

miss the rawness of The Sweet Hereafter, but can understand its elimination:

where those characters had to aimlessly try to project their disdain on anything around,

the inclusion of an enemy, Richard Strout (Mapother), gives some unease to the characters

peering directly at a defined antagonist.

Todd Field succeeds in making the camera into an innocent

in this story. Where other directors -- Mr. Egoyan included -- would have remained on

certain scenes where actors and actresses are working on an Oscar nomination, Field steps

back. This is one of the most controlled directorial pieces of 2001. When scenes begin to

feel uneasy and turn the director into an emotional voyeur, Field fades to black. He does

not want to elicit fake sentiment out of the audience -- this is by no means a Patch

Adams or Stepmom, the emotions that are created by this film are as

believable as anything you might read in a John Steinbeck novel.

In the Bedroom is based upon the short Story "The

Killings" by Andre Dubus, a writer whose short stories has become an obsession for

the director. During his tenure in the American Film Institute, Field made a series of

Dubus stories into short films. After reading "The Killings," he decided he had

found the one that transcended its short form (17 pages) and needed to be made into a

feature film. After taking a draft from Robert Festinger, Field rewrote the script into

this final version, where he chose to emphasize the emotional side of the story instead of

the thriller that Festinger was more fixated on.

The film's implosion into vigilantism is still a little

worrisome, but the way Field and his actors deal with it keep the film from losing all its

attributes in a poor third act. Tom Wilkinson, who had been remarkable in the film's first

hour, takes control of the second and pursues a passionate performance of the violent side

of Matt Fowler. Sissy Spacek has received most of the attention for the film -- and she is

definitely great in the film -- but the true anchor of the movie is Wilkinson.

In the Bedroom comes in a time that could not be

more prescient. In a time when even the most rabid pacifists are turning to "an eye

for an eye" aggression towards terrorist sects, In the Bedroom sits in

theatres for audiences to see what violence begetting violence can do. The movie may be

slow and deliberate, but that dormancy makes it all the more rewarding in the end.

BUY THIS FILM'S

FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM

|

|

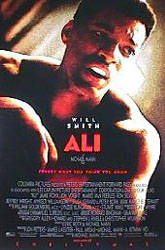

Ali

(Dir: Michael Mann, Starring Will Smith, Jamie

Foxx, Jon Voight, Mario Van Peebles, Ron Silver, Jeffrey Wright, Mykelti Williamson, Pada

Pinkett Smith, Nona M. Gaye, Michael Michele, Joe Morton, Barry Shabaka Henley, Giancarlo

Esposito, Laurence Mason, Candy Brown Houston, Michael Bentt, James Toney, Charles

Shufford, Paul Rodriguez, Bruce McGill, LeVar Burton, and David Cubitt)

more

BY: DAVID PERRY |

In 1963 Cassius Clay announced that he was "the

greatest," a name that still to this day stands as his nickname. The only time that

this multi-monikered icon picked up a new nickname was in 1964, when people began calling

him "the champ."

Ali, Michael Mann's biography of Clay, begins in

1964 when the young 22-year-old boxer defeated Sonny Liston for the World Championship

Title. The film then proceeds to tell the next decade in the roller coaster life of

Mohammed Ali.

There are many things that happened between 1964 and 1974

for Ali, he established himself in Islam, changed his name, divided himself from one-time

friend Malcolm X, went through three wives, scorned the draft and the Vietnam War, and

fought named like Liston, Joe Frazier, and George Foreman. Taking aim at just this period

of the man's life is a huge and notable effort, but the fact that Mann never even glances

beyond the decade deprives the story from ever really taking in the soul that Mann strives

to include. Sure, we momentarily see an adolescent Clay in a segregated bus and read some

titles on what happened in the year after "The Rumble in the Jungle," but never

does Mann and co-screenwriter Eric Roth take the time to explain to the audience what this

meant to his life up to that point.

The Roth/Mann script comes from a huge 200-page draft

written by Stephen J. Rivele and Christopher Wilkinson that attempted to cover the entire

life of Mohammed Ali. This draft, which itself was a rewrite of Gregory Allen Howard's

biographic script, could have made an expansive and detailed exploration of the ups and

downs of Ali's career and life, but it was scrapped for something more along the lines of Nixon,

where we just look at one point in the subject's life. Unlike Nixon (which was

co-written by Rivele and Wilkinson), however, the period is never really put into any

perspective -- Ali is like a highly presumptuous project, where the audience is expected

to know every move in his life like they have spent years researching it. For an energized

companion pieces to a course on 20th century icons, Ali might be an interesting addition

to a small curriculum on the man, but as a simple biography it feels highly neglected.

The movie is worth seeing, nonetheless. It features a great

performance from Will Smith in the title role and a barrage of interesting set pieces.

Where the movie fails to control its storytelling, Smith comes in to redefine the idea of

impersonation. The actor put on 35-pounds of muscle to bulk up to Ali's size in his prime

years. The actor does not terribly look like Mohammed Ali (as a matter of fact, he looks

more like the actor who played a young Ali in the horrible 1977 film The Greatest),

but he has taken the time to learn the speech patterns and mannerisms of the real man. For

that reason, even when we are not completely convinced that the image on the screen is

that of Ali, we are convinced that it is his personality on parade.

Giving an equally as impressive turn is Jon Voight as

Howard Cosell. The actor has donned layers of makeup to look like the toupee-wearing

sportscaster, and has done as much work to get the voice of his precursor right -- for the

most part, it is hard to believe we are watching Jon Voight and not some highly talented

impressionist.

Probably the only reason, though, that this movie ever

comes near success is the workhorse direction brought by Michael Mann. For two decades,

the director has worked hard to make some of the finest stylized dramas for mass

consumption. It's too bad that people were not willing to sit down for his most adult

work, The Insider, probably bringing the director to taking this more

crowd-pleasing project.

Ali has a built in audience, and showing the man

in a good light is all that is really needed. Mann still does some work to keep the movie

grounded in reality -- I especially liked the way he humbles the settings for Ali,

even as a renowned boxer his race left him in some of the less-affluent hotel rooms and

apartments. And the photography by Emmanuel Lubezki brings a great deal of interesting

lighting and film stocks to match the various points in Ali's life.

Considering the high expectations that went into this film

and weight Mann probably found as he began to tackle it, I suppose it's not hard to see

why the film is ultimately so unfulfilling. There are those who expect a complete story

and those who want the abridgement, there are those who want an affectionate portrayal and

those who want a biting one -- Mann shows his expertise as a filmmaker by still making a

mildly pleasing film while attempting to juggle everyone's predisposition. Now, its time

for him to get back to what he does best -- the flashy, novel dramas of a society about to

burst.

BUY THIS FILM'S

FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM

|

Year in Review Essay:

Belle Époque

Cinema 2001: A Great Year for Movies -- At

Least the Ones in a Foreign Language

As I began putting together my OFCS ballot this year and

setting up some things for the Golden Brando Awards, it suddenly hit me: the studios were

nearly worthless this year. I've been pretty active complaining about them for a few years

now, but this time around I cannot help but feel stifled at how poor their slate was this

year. When I wrote that last year had an insurmountable abundance of fine independent

films, I never imagined that I'd be reiterating it the next year.

Today I looked at my top ten list of 1996, the supposed

year of the independent films. I then compared it to the top ten list I have for 2001 so

far: both years are almost devoid of any studio products. 1996 had only none -- 2001 has

two, Wes Anderson's The Royal Tenenbaums and Steven Spielberg's A.I.:

Artificial Intelligence. If I include the ten more from "honorable

mentions," 1996 has Milos Forman's The People vs. Larry Flynt, and 2001 has

two more, Steven Soderbergh's Ocean's 11 and Sean Penn's The Pledge. Oh,

and for the record, anyone who thinks The Royal Tenenbaums, Ocean's 11,

or The Pledge feel like a studio effort has not seen enough studio films this

year.

First off, kudos to the people at Warner Bros. -- they have

proven that, despite having some major setbacks in box office sales from some flops (not

including the dreck of Harry Potter, of course), they have released the best

studio films for the year. Ocean's 11, The Pledge, and A.I.:

Artificial Intelligence were all made by them: David Mamet's Heist, Frank

Darabont's The Majestic, and Dominic Sena's Swordfish. Oh, there have

been many bad films from them, but the fact that they were even willing to give Sean Penn

a chance to make another film gives them the rights to some praise.

But, what does this have to do with my central thesis this

year, that 2001 was a "belle époque" ("beautiful age") outside of the

studios? Well, after those four fine films in my top 20, I'm hard pressed to name more

than five additional studio films I would call great (for the record: John Singleton's Baby

Boy, John Dahl's Joy Ride, Pete Docter's Monsters, Inc., Frank Oz's

The Score, and the Farrelly Brothers' Shallow Hal).

I chose the name "belle époque" because, besides

the many fine independent films, the real treat of 2001 was in the imports. Thank you

Sweden, France, Germany, Iran, Columbia, Hong Kong, Canada, Australia, England, and

Mexico, without the films exported from those countries, I might have to pull a Janet

Maslin retirement for the exact opposite reason. France was the largest supporter of

Xenophile addiction, they brought me pleasure in Francis Veber's The Closet,

Catherine Breillat's Fat Girl, Agnès Jouie's The Taste of Others,

Claude Lanzmann's Sobibor, 14 October 1943, 4 p.m., Patrice Leconte's The

Widow of Saint-Pierre, Jean-Pierre Jeunet's Amélie, Agnès Varda's The

Gleaners and I, Dominik Moll's With a Friend Like Harry, and especially

François Ozon's Under the Sand. Australia was also surprisingly strong this year

(not that they do not have good movies from Oz, just that movies are so rarely brought to

the states in a wide fashion) with Innocence, The Dish, and Moulin

Rouge. Until September, my choice for the best film of the year was a foreign film,

Alejando González Iñárritu's Amores Perros.

When I began the year singing the praises of Liv Ullmann's Faithless,

Henry Bromell's Panic (so independent that it did not get a distributor until

after it had played in festivals and on HBO), The Pledge, and Amores Perros,

I never thought that I'd have to wait nine months for a movie to even compare to the likes

of the foreign language films in the earliest months.

But then big-name directors came in. David Lynch (Mulholland

Dr.), Joel Coen (The Man Who Wasn't There), Robert Altman (Gosford Park),

Steven Spielberg, Wes Anderson, and John Singleton. The GBA Best Director list I sit on

right now features three of those aforementioned directors and two foreign filmmakers.

Young talent was not necessarily nonexistent; they just did

not leave a huge mark. Terry Zwigoff made his first fictional film, Ghost World,

actor Todd Field made In the Bedroom, Jean-Pierre Jeunet brought us Amélie,

Jonathan Glazer left music videos for Sexy Beast, and Wes Anderson made his third

film, The Royal Tenenbaums, into another masterpiece of quirky comedy.

Savoring these films only makes me look at the wide

releases in even more disdain. Of all the films I have named in this essay thus far (and

this is, by far, the most name dropping I've ever done in one piece), only a handful never

went through platform releasing (even Moulin Rouge, one of the few imports to get major

studio backing, opening strictly in New York and Los Angeles at first).

So, as a way to restrain myself from anymore name dropping,

I'd like to turn to my rant on platform releasing. I am mainly focusing on The Royal

Tenenbaums, a Touchstone release that has still not opened in more than a few dozen

cities. I work two cities right now, Nashville and Knoxville, neither of which have this

movie yet (I caught the film in Atlanta, the only city in the Southeast with the film).

But that is not keeping Touchstone from continually airing advertisements for the film.

They are aggressively pushing a film that no one can see in most cities!

This is not a film like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

where people are going to become hyped for the film by this, this is an offbeat film from

the makers of Rushmore -- yeah, they're going to get some Ben Stiller and Gwyneth Paltrow

fans to join the Wes Anderson/Owen Wilson audience, but they would have come had they just

released the film on the same day everywhere. Hell, Warner at least had the decency to

release The Pledge everywhere on the same day, not trying to hint to the art house goers

that they had a gem on their hands.

I'm still waiting on a few films -- Iris, Black

Hawk Down, I Am Sam, Donnie Darko, and The Shipping News

-- because they are still in limited release and the studios have not sent out screeners

to my doorstep. If the distributors of these films had not chosen to go with a platform

release schedule, I would have been able to vote on them for the OFCS awards, possibly

giving them another award to tout in their Oscar ads. I am maligned at them for this: not

only do they take away the glory of having seen everything before the end of the year,

they have also failed to give a good enough slate in the early months to even come near

eclipsing the imports and domestic indies that they try so hard to defeat in the critic's

awards.

Reviews by:

David Perry

©2001, Cinema-Scene.com

http://www.cinema-scene.com