|

Fat Girl

(Dir: Catherine Breillat, Starring Anaïs Reboux, Roxane Mesquida, Libero De Rienzo, Arsinée Khanjian, Romain Goupil, Laura Betti, and Albert Goldberg) BY: DAVID PERRY |

| Cinema-Scene.com > Volume 3 > Screeners '01 #3 |

Cinema-Scene.com

Special Edition

Screeners '01 #3

Artisan: Startup.com.

Avatar: Kandahar.

Cowboy Booking International: Down from the Mountain, The Endurance: Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Expedition, Fat Girl.

DreamWorks: The Curse of the Jade Scorpion, Evolution, The Last Castle, The Mexican, Shrek.

Fox Searchlight: The Deep End, Sexy Beast, Waking Life.

Lions Gate: Lantana, Monster's Ball.

MGM: Bandits, Ghost World, Hannibal, Legally Blonde, No Man's Land.

Miramax: Amélie, Apocalypse Now Redux, The Others, With a Friend Like Harry.

New Yorker Films: Life and Debt, Smell of Camphor, Fragrance of Jasmine, Sobibor, 14 October 1943, 4 p.m., The Town is Quiet.

Newmarket: Memento.

Universal Pictures: A Beautiful Mind, K-Pax, Mulholland Dr., Spy Game.

USA: Gosford Park, The Man Who Wasn't There.

|

Fat Girl

(Dir: Catherine Breillat, Starring Anaïs Reboux, Roxane Mesquida, Libero De Rienzo, Arsinée Khanjian, Romain Goupil, Laura Betti, and Albert Goldberg) BY: DAVID PERRY |

Adolescence is filled with hormones that cannot be quenched. Porn, fondling, and ultimately sex run through the timeline of a youth’s diary -- whether they meet these intentions or not is unimportant, they are always on the mind. There was a time when sex was a quiet, backseat thought for the youths of America, where sex education was the work of schoolyard conversations and locker room boasting. The 1960’s changed everything with the increased use of contraception and the openness to the anatomy and psychology of sexual intercourse.

Fat Girl, an import from France, feels like the penultimate step in the transgression of film from The Many Loves of Dobbie Gillis to Blue Lagoon to now. Its strong view of this time in a young girl’s life is meant as more of a delving into reality than as some voyeuristic touch on child porn, the only place cinema can go to one-up this film. It does not mean to be exploitational, which is a similar statement that must be reiterated with the release of any Catherine Breillat film.

A director willing to use sex as narrative foreplay, Breillat has made a career out of dancing around the lines of pornographic and dramatic films. Her movies, especially 1999’s Romance, often turn off viewers unwilling to have sex thrown out at them in such a frank manner -- an unfortunate byproduct of Breillat’s films receiving press over the overt sexuality means that too many people enter the theatre expecting something titillating only to find a movie obvious in its detrimental view of sexuality.

Fat Girl (a title inexplicably given to its English-language release; the actual title is À Ma Soeur!, or To My Sister!) follows suit with Breillat’s films even if some of the actions seem toned down because of the age of the protagonists she is now working with. The movie follows two sisters and their fears, intentions, and likely fates in dealing with their first sexual relationship. Elena (Mesquida), the thin and beautiful 15-year-old, latches to beliefs in love for her first time -- she imagines finding the romance of her life and giving herself to him. On the other hand, Anäis (Reboux), the chubby 12-year-old, does not want to love the man who takes her virginity -- perhaps as a product of her unattractiveness, she disdains the baggage that comes with love and sex as one, therefore giving away something extra to that thief of her cherry.

In marathon speed, Breillat introduces these characters and their feelings. Before long, we are privy to the relationship that will become Elena’s first time. While on a family vacation to some seaside resort, Elena falls head-over-heels for Italian college student Fernando (De Rienzo). It only takes three minutes before they are pawing each other at a restaurant.

That night, Anäis agrees to let Elena enjoy her chance for love -- with dusk, Fernando sneaks into the shared bedroom of the sisters and begins convincing Elena that he loves her and deserves her body. Elena, almost because she wants to believe it, holds on, pleading for the remnants of her chastity -- Fernando, by reminding Elena of what all the girls do, is able to get something out of Elena even if it is not through vaginal penetration.

All this happens in the first third of Fat Girl -- the remaining hour is meant to both create some sort of closure to the proceedings and then turn all of the newfound tranquility on its head. Catherine Breillat is willing to look at her two young girls with a foreboding affection, but her glance at the audience is far more hostile.

With its end, though, Fat Girl feels forced, and that is a

huge problem considering how embracing it felt in the beginning. I’m not saying this

from merely an adverse reaction to the film’s surprise finale, but from a feeling

that the movie never completely meets all its intentions. Other movies, of far differing

genres, have looked at the bleakness of a French holiday (With a Friend Like Harry and

Under the Sand come to mind) and the problems of obesity (Monster’s Ball

and even Shallow Hal present a more likely vision) with more ingenuity.

Breillat instead is only willing to touch on her characters’ sexual awakenings and,

in the end, leaves the characters and the audience shafted.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

|

Life and Debt (Dir: Stephanie Black, Narrated by Jamaica Kincaid) BY: DAVID PERRY |

They live in complete poverty, a day-to-day life that involves working for slave wages as opposed to the push of policing guns. And yet, we go to their country as a holiday destination.

I went to Aruba this past summer and soon learned the difference between that Caribbean island nation and Jamaica -- nearly everyone in my party, at the hotel, and, of course, the biased tourism guides spoke of what a horrendous destination Jamaica was. While visiting, a person can enjoy the same sunny weather, low humidity, unending beach, clear blue water, and souvenir shopping as in Aruba. The big difference is that in Jamaica, you get to see people wallowing in grief over their lives -- not only has the place become a hotbed of poverty but also of crime.

The tumultuous lifestyle of the Jamaicans is covered in Stephenie Black’s Life and Debt. The documentary, based upon the book A Small Place by Jamaica Kincaid, examines the way the rich countries have chosen to exploit the financial inefficiency of the third world nation. When Jamaica became a soverign country free from the rule of Great Britain, their economy nearly collapsed -- the great mother country was no longer willing to take care of them. In debt, Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley signed away most of Jamaica to creditors. Like a man attempting to pay a credit card debt with another credit card, Manley had to take out loans to pay loans.

Manley is more than willing to pass the buck -- and it is easy to see that the film sympathizes with the problem during his administration. He blames the large Western nations, who have used Jamaica for cheap labor and easy sales. The onetime proprietorship that England extended has now turned into the relationship of a economic competitor. The people of Jamaica base their economies on bananas, milk, onions, and chickens, but the American corporations see any sale that is not for American needs as a sale lost. More than anything, according to this film, Chiquita, Dole, and Del Monte have worked as hard as possible to quench any non-American banana business in Jamaica.

The International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank now own almost every facet of the Jamaican economy -- those few local businesses are now barely surviving. And the only ones that are making money: franchises like McDonalds.

It is hard not to empathize with the Jamaicans -- their plight is almost completely the creation of our domination of the world economy. As we attempt to enter a globalization economy through the World Trade Organization, movies like Life and Debt try to remind us what a cooperative like the WTO means to small nations. It would look a great deal like the International Monetary Fund, which has become the main culprit of Jamaica’s financial collapse. Any policies for the IMF take an 80% approval for a change. As is, these policies are meant to help only the richest nations and those nations -- America, Western Europe, Japan -- make up more than 80% of the vote.

But, before someone takes me to task for this review,

I’m still supportive of the WTO. Watching Life and Debt made me think about

what could be wrong with such a collaborative, even if I consider it to be a highly

integral part of a continued growth of the world economy. I do fear that this could

further hurt the people of Jamaica and other small nations where our clothing and small

products are made; I can only hope that the money-hungry leaders of the WTO will be

willing to watch Life and Debt before they attempt to crush all small

competition.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

|

No Man's Land (Dir: Danis Tanovic, Starring Branko Djuric, Rene Bitorajac, Filip Sovagovic, Georges Siatidis, Serge-Henri Valcke, Sacha Kremer, Alain Eloy, Katrin Cartlidge, Mustafa Nadarevic, Simon Callow, Bogdan Diklic, Tanja Ribic, and Branko Zavrsan) BY: DAVID PERRY |

The comparison of Hollywood blockbusters and the European dramas that shame them has never been more persistent as a glance at Behind Enemy Lines, a 20th Century Fox production that opened earlier this month, and No Man's Land, a Bosnian production preparing for a hoped Best Foreign Language Film nomination at the Academy Awards this year.

Each film deals with the idea of being stuck in a Balkan battlefield without any real way to get out. But the key difference is that Behind Enemy Lines is loud and aggressive with its aggrandizing celebration of deus ex mechina. No Man's Land, on the other hand, is willing to sit back and look at the who's, the what's, and the why's that brought its protagonists to this situation. I'm not going to completely rally against the studios right now -- 20th Century Fox did once make a film that could compare to No Man's Land, Terrence Malick's The Thin Red Line in 1998, though nothing from them since has been quite in the same vein (it did not help that the Malick film was a financial disappointment, struggling to find an audience just months after Saving Private Ryan had come out).

Danis Tanovic's film worries about the state of Bosnia and Serbia, not attempting to exploit it for a series of action film clichés. The civil war going on there has never been a major cinematic interest, mainly because most Americans could not care less what was happening so far away. Tanovic does care and yearns to bring this story to the fore. He was a Bosnian soldier and ran the army's film library, capturing some of the most staggering footage of the war for various documentaries. This is his first time as a fictional filmmaker, and his effort has proven to be quite rewarding with a Best Screenplay win at the European Film Awards and the Cannes Film Festival this past year.

At the beginning, Tanovic seems to be documenting to move of a small group of Bosnian fighters. They are lost in the night's fog and must wait before they can continue. When the fog lifts, they find they are staring right into the Serbian lines and are immediately shot upon. One soldier, Chiki (Djuric) jumps in a trench before being killed. He must wait there in hopes that someone from his side will come before the opposition comes.

The Serbians make it there first and begin to set up the trench with a mine under a dead body not knowing that Chiki is there. When they become aware of his presence, after placing a mine under the body of his friend Cera (Sovagovic), he kills one of the two Serbs, letting the other, less trained one, Nino (Bitorajac), survive. Now, the two must remain in the somewhat neutral trench with enemies on both sides and a mine sitting beside them. Matters are made worse when Cera comes back to consciousness and finds he cannot move without setting off the mine under him.

For a film made by a Bosnian army veteran and with Bosnian money, No Man's Land is surprisingly neutral in laying its disdain. Both of the central characters are bent on blaming the other and unwilling to admit any fault of their own side. Tanovic's main idea is that the blame is essentially on ideas, which have brought about hatred between these two sides. Ethnicity has created a war between people who are practically the same (Chiki and Nino soon find that they knew the same girl when they were young). And this is not a film about making everything well by showing these two people can come together once their aggression has been placed aside.

The real admonition laid by Tanovic is on the outsiders in the Balkan war. He brings UN "peacekeepers" and media outlets into the film's second act and shows the audience that they are more willing to exploit the soldiers than anyone on either side of the battle lines. Outside of a caring French UNPROFOR officer played by Georges Siatidis, most of the people trying to supposedly help the stranded the soldiers are opportunistic (like Katrin Cartlidge's TV news reporter) or callous (like Simon Callow's UN general). We are accosted with images of the Bosnians and the Serbs fighting a war partly a product of centuries of hatred and party the product of misguided interveners.

As the film veers into a land too close to 15 Minutes,

Tanovic begins to lose his footing, but almost every minute before then had been highly

affective filmmaking. The director had created a war movie that is not about

grandstanding, but about the miserable fate of people fighting. His final image seems like

something that Terrence Malick would probably have included in The Thin Red Line,

a moving testament to how man's violent creation of war has destroyed the natural

progression of the world.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

|

Smell of Camphor, Fragrance of Jasmine (Dir: Bahman Farmanara, Starring Bahman Farmanara, Roya Nonahali, Hossein Kasbian, Firouz Behjat-Mohamadi, Reza Kianian, Parivash Nazarieh, Mahtaj Noojoomi, and Valiyollah Shirandami) BY: DAVID PERRY |

Bahman Farmanara's career seemingly came to an end twenty years ago when the Shah and the Ayatollah of Iran both decided that he was not a director who could make movies within the state. After taking refuge in Canada, Farmanara went back to Iran without making a movie while out of the country -- his family's inherited business needed him. Since then, he has constantly written screenplays for production, but none of them pass the regulations set by the government. Smell of Camphor, Fragrance of Jasmine is the first Farmanara script to pass the Iranian censoring board since 1978's Tall Shadows in the Wind.

And, as much as I hate to say it, the wait really has not brought much out of the long dormant filmmaker. It could be that the oppression has caused him to lose much of his artistic delights, or that he is just out of practice. However, the new film feels like something created just to reaffirm Farmanara that he is still alive and able to work, even if the film is about him not being able to do either.

A rumination on death, Smell of Camphor, Fragrance of Jasmine stars Farmanara as a long-unemployed film director who is about to get his first chance to work in a long time (hmm, sound familiar). As he begins work on this new project, a documentary on Iranian funeral rituals for Japanese TV, he begins to worry about his own mortality. It does not help that we first meet him on the day before the fifth anniversary of his wife's death.

Farmanara's character is overweight, smokes constantly, and has a heart condition. Though only 55-years-old, his worries of impending death are possibly not undeniable.

He goes around Tehran working on this project, regularly bombarded with reminders that he is not young anymore -- a visit to his Alzheimer's diagnoses mother, a young girl whose baby died in birth. And, as he begins to work on finalizing some of his own matters, he finds that he is currently not at a suitable point to die (for example, his burial plot beside his wife has been sold to someone else).

There is hope found in Smell of Camphor, Fragrance of Jasmine, which keeps the film from becoming a monotonous directorial effort. I liked the way that Farmanara settles down his poor attempts at subtle humor for scenes that feel as relatable as real life. Giving away any of these moments would not be fair to those who actually see the film, but I can say that they are the only really worthwhile parts of the film.

Well, there is one other thing: the ability of Farmanara to

set-up a shot is still fine. He has a good eye for camera placement and editing that help

him to overcome some of the larger storytelling problems. The film is separated in three

parts, with a constant connection that ties them together. While that connection is not

very well defined for the running of the three sections, it is quite nice to look at.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

|

Sobibor, 14 October 1943, 4 p.m. (Dir: Claude Lanzmann, Narrated by Yehuda Lerner) BY: DAVID PERRY |

On 14 October 1943, a group of Soviet POWs led a revolt in Sobibor, a concentration camp just outside Minsk. Their uprising stands as the only known success story in the history of the Holocaust.

In 1979, Claude Lanzmann set out on his grand journey to document the history of Holocaust survivors for the film Shoah. Today we overlook the huge experiment in documentary filmmaking that Lanzmann created -- his movie, which was dedicated to nothing more than people’s memories, has been recreated in hundreds of documentaries on the Holocaust, ranging from The Journey Home to Into the Arms of Strangers: Stories of the Kindertransport. Steven Spielberg now works with group called the Shoah Foundation, which has made it their task to give media for Holocaust survivors to tell their stories so the world can never have an excuse to forget what atrocities happened.

One of the people Lanzmann interviewed in 1979 was Yehuda Lerner, the only remaining survivors of the Sobibor revolt. As Lanzmann began editing his nine-hour cut of Shoah, he decided that the story of Sobibor did not continue the underlying account of oppression and horror that marked each of Shoah’s stories. Instead, Lanzmann decided that Sobibor, 14 October 1943, 4 p.m. should be made as a record of merely Lerner’s interview.

Watching the film conveys much of the frightening storytelling structure that marked Shoah. Lerner is a fine narrator to this story with his impressionable memory of all the events surrounding both his days of life in Sobibor and the day he got out of the place. Lanzmann uses the first half of the film to portray the history of Sobibor and the road that brought Lerner to the camp. The second half, so intriguing that only a churl would not be on the edge of his seat while listening, is just the story of that day in the camp, when Lerner and Soviet officer Alexander Petchersky had to completely hinge their plans on the perfection of Nazi planning and their promptness at 4:00 p.m.

Compared to the weighty length of Shoah, Sobibor, 14 October 1943, 4 p.m. feels like a lighter version. I thank the director for taking the time to tell this story, and, yet, felt stilted by the lack of any more information. Lerner remembers so much -- and he is, to the best of our knowledge, the only surviving member of the uprising -- that you cannot think of another person to give a verbal history of the revolt. Even the stories of the insurgence’s children might be a good appendix to this story.

There is a language barrier involved that makes the film harder to follow. Lerner only speaks in Hebrew, which Lanzmann does not speak. For that reason, the camera remains intent on Lerner as he tells the story and then waits for a translator to tell his story in French, which is in-turn typed in English subtitles. For a film where the man speaking is so keen on telling his story, having to wait for some woman to translate him in a monotone voice is rather aggravating.

But regardless of the hindrances, this is an important

story to be told. Lanzmann and his remarkable hold on the medium allows audiences to

understand what people like Lerner lived through. Watching this film is refreshing, partly

because it is hard to imagine how the story of Sobibor could ever be made into a dramatic

movie. As a documentary -- elitist or not -- the film stands as a testament to the turmoil

and heroism that can never work through the artificiality of cinema.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

|

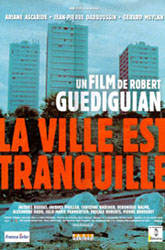

The Town is Quiet (Dir: Robert Guédiguian, Starring Ariane Ascaride, Jean-Pierre Darroussin, Gérard Meylan, Jacques Boudet, Christine Brücher, Jacques Pieiller, Pascale Roberts, Julie-Marie Parmentier, Pierre Banderet, Alexandre Ogou, and Véronique Balme) BY: DAVID PERRY |

Like the Music City, USA, featured so prominently in Robert Altman’s Nashville, French filmmaker Robert Guédiguian has taken the time to make his own love letter to the upheaval and seething violence behind another world city: Marseilles. Perhaps his film, The Town is Quiet (La Ville est Tranquille), is just one part of what could be called the directors-in-love-with-a-depraved-city series that would include Alejandro Gonzales Inarritu’s Amores Perros (Mexico City), Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire (Berlin), Michael Winterbottem’s Wonderland (London), Woody Allen’s Manhattan (New York City), Pedro Almadovar’s All About My Mother (Madrid), and that other big Altman ensemble film Short Cuts (Los Angeles).

Though, despite some pretty unfortunate moments in almost all those films ranging from dog fights to a child’s death to a nun inflicted with AIDS, none of those films really come near the absolute depression of Guédigiuan’s film -- in the Marseilles of The Town is Quiet, there’s political upheaval, racism, labor disorder, foreign domination, homicides, and suicides. Though, what major city does not have all those problems.

And like the Altman movies, Guédigiuan uses an assortment of characters to tell his story as their lives intersect and change each other. At one moment, someone may seem like a mere cog in one story, when scenes later, he takes an important stand in the other section of the film.

The center of the film seems to be on Michèle (Ascaride), a working class Frenchwoman who works at the local fish market. Everyday she rides her motorbike from to and from home, freeing herself from the war zone that is going on inside her crowded apartment. Her husband Claude (Banderet) is an alcoholic and frightened by the current standing of his family -- he barely seems like part of the household most of the time. Meanwhile, her daughter Fiona (Parmentier) lies in a room calling for more heroin to pump into her body. Years of being both a junkie and a prostitute have left Fiona with the inability to survive without a drugs and the addition of a small child into the fold. Michèle, of course, must take on the duty of caring for the child since Fiona is definitely not up to it.

When Michèle runs out of gas on the side of the road one day, a cab driver stops to siphon some petrol to her tank. He is Paul (Darroussin), a hard on his luck former dock worker who has become a shamed soul for old friends and family when he went against his union and accepted a severance package during a strike. Paul soon becomes obsessed with Michèle and decides to give anything for her.

There’s also a plot involving the relationship between Michèle and her ex-boyfriend Gérard (Meylan) and between music teacher Viviane (Brücher) and former North African prisoner Abderamane (Ogou). All the while, though, the main interest is in Michèle’s plight.

This is not a surprise considering that the actress, Mrs. Ascaride, is the wife of the director. For a film supposedly built around all these people’s problems, almost the entire interest of the camera is on Michèle and her now-clichéd problems. For my money, what she’s going through has much better been dealt with, especially in the form of Lynne Ramsey’s Ratcatcher.

The director does have a fine eye for shots of

Marseilles, which has never looked as both stunning and horrible at the same time.

Guédigiuan has made some fine films in the past like Marius et Jeannette, but

this work with all its failed plots and misdirected crankiness feels like a step back for

him. The nouveaux pauvres have never seemed as dingy, and, yet, nothing in

Guédigiuan’s film seems willing to convey a reason that filmgoers should care. Yeah,

it is somewhat interesting that Claude’s father is as communist as a modernist comes

and that strings of Janis Joplin ring the minds of the past, but nothing comes about from

it. The Town is Quiet feels like a film with all the weight of a single class

behind it, but in the end shows nothing more than high-class cinematography united with

low-class storytelling.

| BUY THIS FILM'S FROM AMAZON.COM |

REVIEWS OF THIS FILM |

Reviews by:

David Perry

©2001, Cinema-Scene.com

http://www.cinema-scene.com