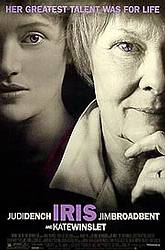

Director: Starring:

OTHER REVIEWS: Contact The Iron

Giant Raiders

of the Lost Ark Star

Wars: Episode I -- The Phantom Menace |

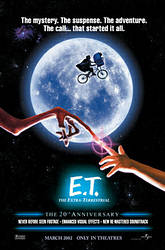

E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial BY: DAVID PERRY The first film my parents took me to was Beastmaster (I don't know what possessed them to do that), followed by Return of the Jedi and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial. All three films opened over the course of a year, but today, I only remember sitting in the theatre for one of the movies. To this day, I remember the awe I was in sitting and watching E.T., the way I felt like I was watching more than simply a motion picture, but an incredible exercise in imaginative cinema. Shot at low angles to simulate the view of a child, E.T. turned into the most impressive work of American cinema in the early 1980's, creating a family film that not only gave a splendid view to the children, but also transported the adults to their childhood. Countless rip-offs followed ranging from Roland Emmerich's Joey (aka Making Contact) to Randal Kleiser's Flight of the Navigator to Stewart Raffill's Mac and Me. All of them tried to recreate the magic in Steven Spielberg's masterpiece but none ever came close. Now, on its 20th birthday, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial comes back to theatres to move its vision onto a new generation of filmgoers. The last time I watched the film was directly before high school when I was in a debate over the best film of 1982 -- E.T. vs. Das Boot, noticeably no one called upon Gandhi, the film that actually won Best Picture at the Academy Awards. Back then, I was reminded of the pleasures that came with watching it the first time. Again, watching it now, for the first time on the theatre screen since I was a small child, E.T. causes all the emotions of that first viewing to come flooding back. It is a no-qualms manipulative film, but it is also one of the best crafted of them all. Stating that there's nary a dry eye in the house following this movie is not an overstatement of its impact. Steven Spielberg has made a career out of manipulation through various stages. He's been the Turk of action nouveau (Duel, The Sugarland Express), redefined the big-budget blockbuster (Jaws, Raiders of the Lost Ark), moved into adulthood (The Color Purple, Schindler's List), and become a kid again (Hook, Jurassic Park). There's not an entry in his oeuvre that doesn't use some form of audience manipulation to get the needed audience reaction. What sets Spielberg apart from manipulators like, say, Tom Shadyac and Ron Howard is that Steven Spielberg has crafted his work into an art -- he is not using contrivances for a response to hide the fact that he otherwise has no substance, but instead uses manipulates the audience so that their reaction is akin to the one his characters are feeling. The only movie that makes me tear up every time I watch it is Schindler's List, where the audience feels like it sharing the same emotional effect as the director is. Alienation has been a theme is some of Spielberg's works ranging from Close Encounters of the Third Kind to Empire of the Sun. E.T. is, perhaps, his best structured of these works, even considering the remarkable work he did last year with A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, which reworked the alien character to a robotic boy. I often criticize the director for relying on similar shtick, but when he gets it right, it can be magnificent. But this is not a success completely dedicated to the work of Spielberg, a collection of other filmmakers helped turn this into the experience it is. Screenwriter Melissa Mathison gave depth to the story; effects operator Steve Willis fashioned a character that feels more realistic than many actors; vocal artists Debra Winger and then 77-year-old Pat Welsh created a voice, sounds, and even a purr that turns a childish entity into a wise explorer; cinematographer Allen Daviau mixed lights, darks, and gray steams that set the needed atmosphere; and composer John Williams scored childlike innocence with awed-excitement unlike anything else he has done. Child actors Drew Barrymore and Henry Thomas give performances far beyond their ages, making it easy to see why they are the only two of the cast who have catapulted to some fame since 1982. Nevertheless, when the dust clears, the lights flicker off,

and the credits begin to roll, the real excitement brought by E.T. can be found

in nearly every face looking up in wonderment. A literature professor of mine once mused

that he'd give anything to be able to relive the experience of reading Romeo and

Juliet for the first time again. E.T., in that way, is an artistic

breakthrough unto itself -- with every viewing, that same experience comes through. And

there's nary a dry eye in the house. |