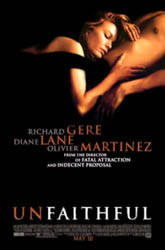

Director: Starring:

OTHER REVIEWS: Faithless In the

Bedroom Innocence A Walk

to Remember |

Unfaithful BY: DAVID PERRY One of the reasons Adrian Lyne has become one of America's more successful filmmakers is that he is as much a moralist as a voyeur. He captures characters in the throes of intense carnal desires and then makes them atone for their sins. Despite the growing agnosticism in this world, Americans still grasp to some deep-rooted beliefs in morality and the hellfire that can follow for the wayward. For this reason, Lyne's fight to adapt Vladimir Nobokov's Lolita is one of the least surprising choices of his career -- Nobokov also had a resolve to look at the way people have digressed and the way they must ultimately pay for it. Claude Chabrol, the Nouvelle Vague Hitchcock, had his own touches with Nobokavian moralizing when he made La Femme Infidèle. Now Adrian Lyne makes his second most predictable choice by loosely adapting the Chabrol film for the screen, with his voyeuristic sexual urges, of course. Connie Sumner (Lane) is a relatively happy Westchester County housewife. Her husband Edward (Gere) has seemingly made enough money in his armored car business to move his family to a posh estate in the suburbs, allowing Connie with the freedom to stay at home taking car of son Charlie (Per Sullivan). But with great freedom, sometimes, comes great boredom -- everyday Connie finds herself commuting into the city so that she can take care of a little shopping. One day, in the midst of the worst windstorm known to man, she literally runs into a man during one of her struggles to get a taxi. In the collision, she skids her knees (which become a fixation for Lyne's camera -- perhaps as a nod to Eric Rohmer and his Lolita story Claire's Knee) and enters the young man's apartment for a little first aid. Almost instantly, the sexual energy can be felt between the two -- Lane is vibrant and Martinez, as French bibliophile Paul Martel, has the smooth satisfaction of a long-working lothario. He quotes a little Omar Khayyam ("Be happy for this moment: this moment is your life") after unconvincingly pointing her to the Kubaiyat as if he had not placed it there for this very occasion. She is smitten but faithful -- the same cannot be said for their subsequent meetings. Soon they are having sex in café bathrooms and in empty movie houses -- Connie finds herself digging herself into lies that become harder and harder for Edward to digest. Unfaithful has so much more waiting to come out -- like a perfectly tuned mystery novel, it has the all-knowing compassion of a author-deity and the fortitude to not drop everything at the wrong time. Lyne and screenwriters Alan Sargent and William Broyles, Jr., never really rely on much contrivance, instead wallowing in a melodramatic resolve built by scenes of happy domesticity and searing sex. The change in pace at the film's midpoint, similar in many ways to Robert Zemeckis' What Lies Beneath, captures an emotional peak that stands both virtuously and carnally; and the ending harkens back to another Broyles screenplay that also knew that the world neither knows nor cares what path a single person goes on. It's Chabrol with touches of Steinbeck and Nietzche. Adrian Lyne and cinematographer Peter Biziou create much of the tension through filters, special lenses, and, in some cases, a patch of smoke. Never in the film does it truly feel staged and yet every facet of its production, every frame has the look and feel of a duteous director and his l'artifice des auteur. At every moment, Lyne et al. are working to create visuals that could never feel true, but successfully refrains from throwing the audience out of the picture. From an artistic standpoint, Unfaithful is his most technically distinguished work yet. Much of the non-visceral satisfaction, however, comes from Diane Lane's performance, which far exceeds what anyone would expect from the normally passable actress. She embodies the inner-struggle of la femme infidèle with the type of immovability that Celia Johnson created in Brief Encounter and, more recently, was given an age change by Julia Blake in Innocence. She goes through a kaleidoscope of emotional changes throughout the film (in some cases, simply within scenes) that places her along side the equally devastating Lena Endre performance in last year's Faithless. Unfaithful delivers a continence unseen by

American cinema -- the way it frankly deals with infidelity is heartening for anyone long

disturbed by the way Hollywood marginalizes sex into a Dawson's Creek mentality.

Adrian Lyne, much like the film Stanley Kubrick tried to make with Eyes Wide Shut,

has directed films about sexual peccadillo and violent punishment. One character in the

film comments that "things like this always end terribly." She thinks, like the

rest of a moralizing America, that a minor tryst can inadvertently bring the worst form of

retribution to the least morally askew people. |