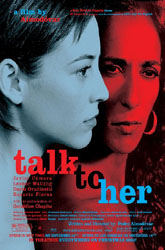

Director: Starring: Release: 14 Feb. 03

|

Daredevil BY: DAVID PERRY As adapting television shows becomes a forgotten fault of the 1999s, film producers intent on their next possible series have turned to comic books. Instantly, they can have a base audience, a series of storylines, and commercially viable merchandise. By comparison, the dour Batman seems dark, dingy, and oh-so-1989. And if the commercially-minded production of these films seem to be in line with the Reagan/Bush '80s, the dumb, flashy, but still commercial, 21st century superheroes seem perfectly in tune with the consensus on our current president. Daredevil, the latest in the drove, is the dumbest. Where Spider-Man worked under the venue of existentialist drama (or at least as existential as pop art gets), Daredevil just seems sad and listless. Call it Sartre's Nausea for the 90210/Dawson's Creek generations, but without the slightest interest in posing the personal anguish over the lead's feelings. Different companies were behind Spider-Man and Daredevil, which brings me some relief in my fear over X-Men 2, The Incredible Hulk, and the other Marvel Comics properties currently going through pre-production. I want to blame 20th Century Fox for turning a seemingly interesting comic book character into a boring, simpleton in a red suit. Daredevil, as best I can tell, is a character worthy of the heights -- no pun intended -- Sam Raimi brought to Spider-Man. But Mark Steven Johnson's vision of Daredevil is more Schumacher than Burton, more bubblegum than molasses. When this superhero does his job, most of the visuals are on the technical achievement coupled with the fast editing of an ADD kid. Nothing is subtle within the film, which would be acceptable if this comic book adaptation were aimed at kids. Considering the violence and sex within, the kids must be growing up fast or this is meant for the true fans who grew up with Daredevil. I cannot speak for that fan, but I can say that this Daredevil is a waste of time for the uninitiated. Maybe the destitution is a nuanced reflection on the original. Maybe all this lackluster confusion comes from the original frames. Maybe the drawn Daredevil was just as boring and murkily presented as this one. Much of the dissatisfaction of watching the film comes, I think, from the cast. How is it that Colin Ferrell, a career decomposing in every American film he appears in, is the most memorable thing about a movie that stars Oscar winner Ben Affleck, Oscar nominee Michael Clarke Duncan, and Emmy winner Jennifer Garner? He chews up the scenery as a manic second-tier villain worthy of Jack Nicholson's first-tier Batman work. The writers give him the worst dialogue in the film -- though there's still much to go around for the rest of the cast -- and he makes it Shakespearean. Affleck spends most of his time playing Daredevil in an introspective pose (is that the character's blindness or his aimlessness?) before then playing the alter ego Matt Murdock in a pained introspective pose. Even when he's having lunch with a constantly joking Jon Favreau, his personality seems DOA. And Garner doesn't help either, though at least the writers admit her inability to play two levels by essentially making her superheroine Elektra little more than her normal self in skintight leather. Their romance seems more puppy love than super-love, but in a world where the superhero has issues that weigh on him more than anything else, who can blame an old flame for calling him on the phone to break up? At least on the phone, she can act like his inability to look her in the eyes is out personal shame instead of more important personal issues. Spider-Man -- and I do hate constantly comparing one good film hero to

a bad one -- at least felt real despite all the fancy special effects (as I said in my

review of that film, my greatest regret was that the CGI looked so bad that they took away

from the perfected reality Sam Raimi had created). Daredevil is pained, or so the film

tries to remind us in every single scene. His pain, I suppose, is meant to make his task

seem more important. Instead it just makes watching the film feel like watching a manic-

depressive dress in red leather and play Gargoyles on skyscrapers. |

|

| ©2003, David Perry, Cinema-Scene.com, 14 February 2003 | ||