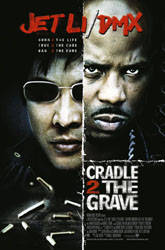

Director: Starring: Release: 22 Nov. 02

|

The Quiet American BY: DAVID PERRY "This is

the patent age of new inventions Most Americans certainly see the Vietnam War as a proxy conflict in the Cold War. The interventionism seems (retrospectively) acceptable under the umbrella of an international Red Scare. What is often lost, though, is the past of Vietnam in the 20th century and its threadbare attempts to survive in a postcolonial world. Graham Greene's novel The Quiet American, written in 1955, was an early effort in unveiling the American presence in one nation's fight for independence. When Greene tackled Franco-American-Vietnamese relations, Dien Bien Phu was merely a year in the past, and Vietnam looked to be on the verge of reunification under the banner of Diem and Minh. Greene, however, noticed the odd way Americans were pitted in the middle of the affair. Even before the pangs of communism looked probable in North Vietnam, there was a bit of U.S. interventionism involved, even if it meant hurting the French establishment in their colonial possession. The novel, which follows fictional British journalist Thomas Fowler during the war with France, became an invaluable guide for anyone trying to cover the Vietnam affair for any news organization. Not only did the book work with the history of Vietnam before the Vietnam War, but it also established something important in the mind of those who read it: no one in this conflict is free of blame, no one can be fully trusted. Greene's work was indeed prescient, though the perfection of his foresight may finally be equated by Philip Noyce, who made a new film version of The Quiet American (it was previously filmed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz in 1958) that comes just as America dabbles again with interventionism. Filmed in 2001, Miramax chose to shelve the film after its semi-anti-American sentiment became a problem in the post-11 September 2001 atmosphere. However, having a film about America's quiet interference in the affairs of other nations seems more pertinent now, as war in Iraq begins, than it would have seemed during the beginning of the Afghani conflict. Noyce's film immediately becomes important because it is the only current film other than Bowling for Columbine dealing directly with the problems inherent in such a policy (whether the end product gives merit to such force is in the eye of the beholder). While Noyce's (and, thus, Greene's) anger is aimed at the meddling Americans, it is also important to note that the film makes no secret of the deals made by both sides in Vietnam or the self-serving apathy of the rest of the West. In The Quiet American, no one's hands are truly clean. The Greene conceit -- a symbolic love triange -- serves the film version well by the casting of three actors who seem molded to meet the symbols they represent. Brash but lanky enough to seem goofy and innocuous, Brendan Fraser's Alden Pyle, the mysterious American of the title, plays a fool with grand intentions -- not for a moment does his humanistic approach to interventionism seem rotten in his mind. And, certainly, it wouldn't: he is, after all, meant as the embodiment of the good-intentioned American presence in Indochina, as well as a perhaps unintentional proxy for current American forces abroad. He is perfectly balanced by Michael Caine's Fowler, who is very much the opportunist Brit who Greene criticized nearly as aggressively as the American. Caine, pitching every line of dialogue with weight but the least amount of pretense, delivers one of his finest performances. Most of the film is through Fowler's eyes, which makes him -- faults and all -- the closest thing the audience comes to understanding 1950s Saigon. His approach to the character is said to be an intentional emulation of Greene himself, helping to understand the quizzical sorrow Greene felt for his British cad in the face of growing impotence. In between is Do Thi Hai Yen as Phuong, the Vietnamese dancer dependent on Fowler for money and Pyle for his reputation. Though her performance becomes an afterthought, the achievement is still very much present. Without the strong Vietnamese native to be fought over by the old colonial and the new colonial -- both treating her as a stupid child -- Fowler's distress over Pyle's defiance of his own code of ethics would seem less like the culmination of a growing incapacity among the European colonials and more like the pining of a lothario. If the film lacks the impact of Greene's novel, the reason is not the fault of

Noyce and screenwriters Christopher Hampton and Robert Schenkkan, but instead in the

ambiguity it sets in. While the film is latched to a setting with a defined beginning,

middle, and end seen through hindsight, its impressions are still waiting to be

understood. Like Remains of the Day -- arguably the last great critique of

colonialism, both in literature and film -- this is a work that captures the essence of an

ethical and social belief that seemed mighty understandable at their moment. Time,

however, will be the true critic -- maybe in a few years we'll finally come to terms with

our own quiet, scheming, violent, but well-meaning Americanism. |

|

| ©2003, David Perry, Cinema-Scene.com, 7 March 2003 | ||