Director: Starring: Release: 28 Mar. 03

|

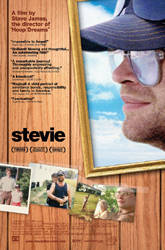

Stevie BY: DAVID PERRY For documentary filmmaker Steve James, Stevie Fielding was a distant memory. During his college years at Southern Illinois University, he felt the need to do something with the Big Brother program. Instead of getting a happy inner-city kid to go play baseball with, James got Fielding, an impoverished runt being juggled around the Pomona trailer homes. After graduating from college in 1985 and taking a job upstate, James left Fielding behind. Stevie, James' documentary on their reunion, is as much about the wasted life Fielding has as it is about James' guilt for being partially responsible. James returned to Pomona in 1995, fresh off the success of Hoop Dreams, the story of two kids trying to realize their dream of basketball success. Fielding hasn't these dreams, his story is more about survival against the odds than it is about meeting any mighty aspirations. James, still feeling guilty for never contacting Fielding during his formative years, worries over this. His time as a big brother may have long passed, but he still feels like it is his duty to ensure that Fielding has the best life. And yet James leaves Fielding again after that one visit in 1995 so that he can head to Hollywood to direct Prefontaine. There is still that nagging guilt within him (and a certain level of exploitiveness shown by the fact that James remembered to bring a camera for his 1995 visit) that makes him return to Pomona two years later. Though the financial and family problems remain, there's another problem plaguing Fielding: he's been accused of molesting his 8-year-old niece. In Stevie, James attempts to understand the troubled life of Fielding and what could have brought him to a crime so unforgivable. James' wife, a social worker specializing in sex offenders, sees him as a monster, and wants more than anything to get her husband out of Fielding's business. But James remains, struck by the way this kid has been allowed to destroy his life. For the next year, James speaks to Fielding's family about their relationship to him and the way they feel about his upbringing, their responsibilities to him, and the possibilities of his guilt in this case. The trail begins with his loving step-grandmother Verna Hagler, who took care of Fielding when his mother Bernice married Verna's son and decided she wanted nothing to do with her illegitimate son. The only connection Bernice ever had with Fielding was in their occasional fights, which almost always ended with her abusing him. It helped that Bernice's trailer was next door to Verna's house. Fielding's stepsister Brenda is the most grounded of the family, as well as the best example of overcoming the elements. She got married, moved to another part of Pomona, and attempted to keep only the slightest connection with Fielding, Verna, and Bernice. It's not that she was abused like her brother -- she was, in their minds, legitimate -- but even she and her husband recognized the destructive elements seething throughout that family. James serves as a companion for Fielding during the processing of his case in the Carbondale court system. However, the camera always remains at his side. Stevie is a very exploitive film, but James' recognition of this, and the remorse he feels for it, becomes part of the draw. He even wonders how this film defines the current relationship that they have: Would he have returned to Fielding's side if it hadn't been for his cinema vérité appeal? Is Fielding only accepting the camera into his life so that James will come back? The most comforting person in this human drama is Tonya Gregory, Fielding's

girlfriend. At first, her speech impediment makes her seem slow and stupid, an implication

emphasized by her relationship to Fielding, but as time progresses her grasp of all around

her seems better than anyone else. She even accepts that her boyfriend is probably guilty

of the crime, but is still drawn to the man inside the monster that she loves. She has

forgiven him from the beginning. It is the power of James' film that, by the end, we all

begin to see what she saw long before us. |

|

| ©2003, David Perry, Cinema-Scene.com, 18 April 2003 | ||