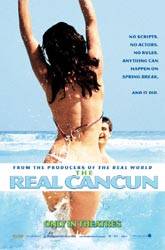

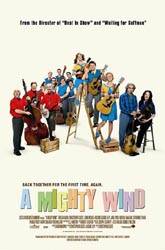

Director: Starring: Release: 18 Apr. 03

|

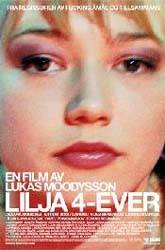

Lilya 4-Ever BY: DAVID PERRY "Now,

dear children, pay attention: There is a deep chasm between Lukas Moodysson's first films, Show Me Love and Together, and his latest, Lilya 4-Ever. Early on, this difference becomes clear when Lilya opens with the aggressively loud lyrics of Rammstein's "Mein Herz Brennt," the polar opposite of the songs that marked those previous films, Foreigner's sentimental "I Want to Know What Love Is" and ABBA's bubblegum "S.O.S." Lilya 4-Ever hasn't the hints of pop that can be found in the underlying liberal treatise of those other two films. At first this seems like a welcomed change, but as the movie progresses, the dramatic change Moodysson has made becomes more apparent and more repugnant. Nevertheless, I can't help but respect Lilya 4-Ever for its deadening, disturbing form of realism, but I also wonder if all the destitution was worth it. This is a movie that remains hauntingly stuck in one's mind days after seeing the film, but the memories are far from fond. This has the earmarks of genius -- a bit of Thomas Hardy remains constantly in mind -- but also the cracks of an overwhelming cynicism and insolvency that makes the film become more distanced and less illuminating. Moodysson's central thesis is strong, but its forgotten within minutes after the film while the memories that do remain only come in reaction to the impoverished feeling it has left in oneself. Lilya (Akinshina) is a 16-year-old living in poverty with her mother in the former Soviet Union (photography was filmed in Estonia). When her mother's boyfriend offers them a chance to move to America with him, Lilya is elated: this is finally her chance to leave the ugliness of her universally lower class city for the land of promise, where she can follow in the footsteps of her idol Brittany Spears. But Lilya's mother isn't interested in bringing her daughter along, promptly leaves the child behind, and renounces all custody of Lilya to the state. In the meantime, Lilya is to be watched by her Aunt Anna (Shinkaryova), but the relative seems more interested in taking the old apartment and sending Lilya to a dump still filled with the trinkets of its recently deceased elderly tenant. She is an outcast in her own community when her best friend Natasha (Berenson) pimps herself out one night and then explains her earned money to her father as being part of Lilya's prostitution. Since this escalates to the equivalent of a Scarlet Letter on her body, Lilya finds her only form of friendship in another outcast, 12-year-old Volodya (Bogucharsky), who lacks any relationship with anyone else (including his father who often throws him out of the house unprovoked) and must get some attention by dealing glue for huffing to the other kids. Since there's nothing else to do when the rest of the world seems to hate you, they are forced to sit in Lilya's new apartment (sans electricity), take the old man's prescription drugs, and talk about their dreams. For Lilya, it remains the allure of the West and the chance for her to succeed with rest of the industrialized capitalist world; for Volodya it seems to be some form of happiness, but one forged within his own world, where he has somehow accepted the desolate surroundings as a mere fragment of the imaginary dream world that this former Soviet Bloc could be. [The succeeding paragraphs reveal major plot elements from later parts of the film. Those who have not yet seen the film are recommended to cease reading.] Lilya turns to prostitution, befriends a compatriot who says he's visiting from his high-paying job in Sweden, is convinced that he can get the same deal for her, travels solo, and then is pimped out to dirty, old Swedish men. But unlike what she had at home, she gets no monetary payment. Instead, the pimp gives her a sparsely furnished high-rise apartment and locks her in. The central thesis seems to be that the promises of the West are just as ugly and desolate as the realities of the East. In both homes, Lilya is confronted with the constant availability of McDonalds, which raises the question of whether it is the sudden push of capitalism into these formerly communist states that has facilitated the slow development they have trudged through. If McDonalds brings "McDomination" (as my old college history professor put it), then Lilya is merely part of the army of those dominated. The only problem is that she has always been dominated by one regime or another, beginning in her childhood inside the Iron Curtain and continuing into her entrance into the "potential" of a Nordic (thus, still leftist) capitalist lifestyle. The continued relationship between Lilya and Volodya (in angel form after killing himself) helps to alleviate some of Moodysson's otherwise ugly moments including a montage of fat, old men coldly pumping their bodies into Lilya (the camera takes her point of view). After a while, the whole things seems so exploitive, so unconditionally sadistic in its presentation that it becomes harder to care about what Moodysson is trying to say. Young Akinshina amazingly carries the burden of her filmmaker's turn towards Michael Haneke's style dramatics (to his credit, Lilya 4-Ever never becomes as respectfully repugnant as Haneke's Funny Games). Like the surprising level of human realism found by Emily Dequenne in the Dardenne brothers' Rosetta, Björk in Lars von Trier's Dancer in the Dark, and Emily Watson in von Trier's Breaking the Waves (as well as most of the amazing actresses Lars von Trier finds for his borderline misogyny), Akinshina brings so much to the character that it becomes impossible to not feel like Lilya's downfall is exacted on the audience as much as the protagonist. She looks tortured and we, having been tortured in our own way by Moodysson, feel just as ready to make the jump as she is. I found it interesting to reflect on the use of music within the single film, beyond the aforementioned comparison to Moodysson's other films. When Lilya is at home, she listens to T.A.T.U., the Russian bubblegum pop singers who have sold more records as artificial lesbians to Westerners than any other Russian act. While the rest of Lilya's life is facile and falling apart, this seems to bring a release, one of giddy, childish fun that is otherwise hard to find. But then there's the Rammstein music that comes in the West. The German band

uses such loud, aggressive sounds that their nightmarish lyrics need no translation to get

their intended effect. This music also serves as a release for Lilya, but one of a more

self-destructive sense. No longer does the music help her to forget, instead, in the West,

it only reminds her of everything weighing against her now. |

|

| ©2003, David Perry, Cinema-Scene.com, 9 May 2003 | ||