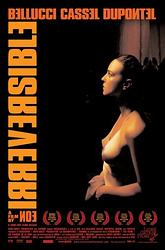

Director: Starring: Release: 7 Mar. 03

|

Irréversible BY: DAVID PERRY Gaspar Noé’s Irréversible is the ugliest, most disturbing film of the year. It is form fitted to create tension, furor, hatred, pain, and agony in the audience. And, believe it or not, it is one of the best films of 2003. That said, I recommend Irréversible to no one. There is no absolutely positive reaction to the film and, most certainly, it is the film most likely to turn off people from ever entering a movie theatre again. I go through countless films a year, many on multiple occasions for edification, socializing, and pleasure. I have no problem watching them in multiples, often from different genres, and have the keen ability to go into the next feature without the previous one, good or bad, weighing on me. That was not the case with Irréversible, which, upon its closing, saw me walk back to my car and drive home. The intended next screening of the evening, Patrice Leconte’s The Man on the Train, would have to wait. And I respect Noé for the very anguish that he gave me. Unlike Funny Games, a Michael Haneke film that reached levels of sadistic fury that even I couldn’t stomach, I almost feel like Noé has earned the raspberries I want to throw at him. I find it fascinating that he was able to provoke such a guttural emotion out of me. I have seen the film three times to ensure the consolation of those attending it in its general release, and no time has the film lessened in its impact. I certainly don’t think I can do it again, but I doubt a fourth viewing would change the absurd reaction I still feel from the film. I have chosen to open my review with these words of grave warning to anyone interested in seeing the film because I don’t want to tack on an “analysis review” warning at the beginning that will ultimately leave someone going to the theatre without hearing my pleadings that they refrain from doing so. I’m certain that there is an audience for the film -- damn, I’m of it, although I find it hard to imagine anyone enjoying the film in the least -- but I’d wager that the vast majority of the populace, including those art-minded individuals reading this review, would not be among them. I’ve tried to make it clear that there are redeeming facets to the film, but sitting through it to experience these facets isn’t necessarily a balanced option. I am hereby instituting my second warning of the review, that in which I recognize that the duration of it will be spent analyzing the film from beginning to end in an attempt, however futile it may be, to understand what it is about the film that works and why it has such a horrible reaction to share with those watching it. It is recommended that anyone still willing to see the film should stop reading. First off, one must speak of the technical novelty that is used in Irréversible, without which much of the film would have, admittedly, been more heinous to experience and make even less narrative sense. Like Memento, the overrated indie charmer of 2001, Noé tells the entire film backwards, although this time it is for a philosophical meaning -- more on that later -- than for a parallel confusion between the audience and the protagonist. The film’s 12 scenes are seemingly uncut (I’m not certain if digital alterations have been made in certain moments to give the scenes the look of an uninterrupted shot or if in fact the film is choreographed so well that it was in fact shot that way), each one showing the events that transpired preceding the previous scene. The first half of the first scene is useless unless one has seen Noé previous film, I Stand Alone. I haven’t and, although I recognize that Noé wanted to give something to finish off what he began in his previous film (and a short), it felt unnecessary and, if the film actually ended with it, as it would have if the film were told chronologically, would have destroyed the flow of the entire work (though, coming off of the film’s dizzying closing/opening credits and the incessant noise that it features -- to great effect I might add -- it does but an unfortunate bit of confusion in the audience at this early moment. This scene is followed by a man arrested and another gurneyed into an ambulance outside a club as men shout threats at them. Then comes “The Rectum,” the Paris gay S&M club that is patronized by Le Tenia (Prestia) and now entered (feel free to come up with the symbols in that sentence) by Marcus (Cassel) and Pierre (Dupontel). Inside, the film features what is probably its clearest misstep in my opinion, a setting that comes off as homophobic (Noé counters that such a reading is unintended) and uses camera movement that is too dizzying for too long. What it works down to, though, is quite possibly the most violently ugly show I’ve ever seen in fictional film. As an innocent man is mistaken for Le Tenia and his head bashed in with a fire hydrant by Pierre, the camera films it all. The skull collapses, the brain matter flies -- although we know nothing of the context, it is so violent that we cannot help but be moved to disgust. The computer editing Noé uses is so seamless (it’s odd how things look so much more real from Gallic and New Zealander graphics houses instead of the U.S. standard of Industrial Light and Magic) that the altercation looks real and thus more painful to digest. The series of scenes that follow for the next 15 minutes -- Marcus looking for The Rectum, his racist outbursts at a Chinese cab driver, his conversation with prostitutes to find get information about Le Tenia, and Pierre’s police interrogation -- begin to flesh out the reasons why the altercation in The Rectum occurred. Scene #7, though, marks the change in the film, allowing us to momentarily see a rambunctious, playful Marcus directly before he sees Alex (Bellucci), battered, bloody on a gurney (notably, our introduction to her, giving us a further understanding of (a) why all this has happened, and (b) what horrible things are coming next). And then there’s the rape, which has been the dividing point, if one can be pinpointed, between those who herald the film and those who hate it. The rape, which I believe is the most realistic, violent thing I’ve ever seen (beating the attack in The Rectum, only 30 minutes after it took that title), seems to last forever. Nine minutes, to be exact, pass as the audience must stare down Alex as she is brutally raped by Le Tenia. It is a visually abhorrent image, but one that took guts from both Noé and Bellucci. She is, after all, the Jennifer Aniston of France (her husband, costar Cassell would definitely be the Brad Pitt; in an odd coincidence, both Pitt and Bellucci give their voices to the animated Sinbad film, though for different language track versions of the film), and seeing her lying there in anguish, pleading for the moment to stop is excruciating. It is a very long nine minutes. The camera is completely stationary during this rape, sitting on the ground while the two actors are in long shot. Before long, the audience is forced to think of something else, anything to get away from the rape. And yet it comes full circle -- my mind thought of a paper a college friend of mine wrote arguing that rape was a partially victimless crime, a statement that brought great discord from me. I cannot comprehend anyone thinking indifferently of rape after seeing this scene. And, as Noé would like for us to consider, Vincent’s rampage begins to seem acceptable considering the crime that has been committed. It is amazing that the Supreme Court once told Georgia that its list of offenses punishable by the death penalty could include airline hijacking and armed robbery but not rape. I don’t think that Noé particularly exploits Bellucci here because there is a technical, philosophical, and narrative purpose to his exposure of the audience to this. Although it is nothing I want to see again, its impact cannot be understated. Those who see it as pornographic are missing the point: only someone deeply troubled, ŕ Le Tenia, would get their kicks watching this. Instead, the scene has a reaction of horror to such an act, not adoration. Although Bellucci is gorgeous in the Yves Saint Laurent dress as she walks into the underground tunnel where she will be raped, the actual action has none of the erotic attraction that one might want from a sex scene that has a partially nude Monica Bellucci. When we do see here in the sensual arms of her lover later in the film, before any of this happened, the image isn’t even erotic then, because her body, and its cosmetic identification with lustfulness and physical perfection, have been forever tarnished by what is to happen to that body later. For that very reason, I recognize that Irréversible isn’t a dime-a-dozen revenge film or merely a novelty trick. It is a film that focuses on the temporal value of past, present, and future. Knowing what we know, nothing in the film’s final half, which is fairly happy, energetic, even lovely, has the impact of its surface. Knowing the future for these people is horrible, as much for what it is as for how happy they are before it. The characters continue to get more and more complex, and their reasons for later actions become clearer.

The film’s ending, which focuses on Alex and she takes a

pregnancy test and then (or earlier) relaxes in a park with children

surrounding her, is the most horrible of all of Noé tricks. Not only is he

insinuating that the worst action, the propagation of the human race into an

ugly, violent world, is part of this vicious circle, but also that in these

moments of joy are memories of their future, and a recognition for the

audience that this happy ending couldn’t be more of a lie. |

|

| ©2003, David Perry, Cinema-Scene.com, 13 June 2003 | ||