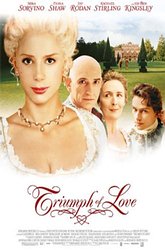

Director: Starring:

OTHER REVIEWS: Charlotte

Gray 42 Up Pearl

Harbor U-571 |

Enigma BY: DAVID PERRY Michael Apted, who turned the simple BBC documentary Seven Up into the most remarkable documentary series ever created, takes another stab at fiction with the British mathematician equivalent of a spy film, Enigma. His best narrative works -- Coal Miner's Daughter, Gorky Park, and Gorillas in the Mist -- have a colloquial quality that Apted strives to perfect; his worst narrative works -- Nell, Always Outnumbered, and The World Is Not Enough -- seem to be lost in an attempt to create something internationally accessible. Apted is a British sociological filmmaker -- his knowledge of particular people, especially his own (as proven by the Seven Up series), has been paramount in his work as a filmmaker. Enigma shares that bond with Apted's best films -- like the others, it is about Brits with conditions pertinent to mainly England in a British setting. Set in 1943, as London felt the regular bombings from Hitler and the Allied ships were often bombarded by German U-boats, the film covers the work of the men and women who toiled in the top secret estate of Bletchley Park. During the war, this small area north of London was filled with verbal and mathematical geniuses in hopes that they could make sense of all the messages coming between the Axis Powers. Like the recent American film U-571, the movie looks predominately at the work around the Enigma machines that Germany used to decode their messages. The American film glazed over much of the history, turning many of the European achievements into grand American fetes. According to U-571, Americans captured the first German Engima machine in 1944 that brought about the turning point of the war; in reality, the Polish revolutionaries (why didn't Wajda get a chance to make this into a movie) stole it from the Germans in 1941 and gave it to the British who struggled to decipher its complicated encoding style. To a much lesser degree, though, Enigma also changes facts. British decoder extraordinaire Alan Turing has been changed to Tom Jericho, a more sellable lead (unlike Turing, Jericho is both a gentile and a heterosexual). Portrayed by comely character actor Dougray Scott, Jericho has a sad-eyed, semi-schizo, finger-pointing persona that automatically brings to mind Russell Crowe's John Nash in A Beautiful Mind, another film that changed a historical figure's Jewish relations and sexuality to make the character more "acceptable." I was not one of A Beautiful Mind's historical accuracy Nazis, who used the film's marginalization of the real John Nash as a way to bash the film (for my money, it was the horrid screenplay and direction that made it such a painful film to watch, not its artistic rewriting of history), though the erasing of Turing in Enigma is rather distressing. The choice is not the complete fault of Apted and screenwriter Tom Stoppard, who are adapting from a Robert Harris novel that used the same replacement of characters. Plus, the historical accuracy Nazis would escalate their anti-Enigma comments if Turing has been placed in the spy drama that ensues in the rest of the film, not to mention the love triangle. All these revisions to the story come at the head of a relationship between Jericho and another Bletchley Park worker, Claire Romilly (Burrows). Seen in flashbacks, she uses Jericho like tissue paper, quickly throwing him to the side when given the heart (and bed) of another man. Distraught, Jericho pleads with Claire to let him back into her life, even offering to tell her all the secrets he knows from his part of the Enigma project. He finally collapses in a mental breakdown, getting a month's leave to regain his senses. When Tom Jericho arrives at Bletchley again, he finds that Claire has been missing for a couple days and the finished decoding of Enigma had suddenly been changed when the Germans switched to a new codebook. Soon he goes into his two other modes: Inspector Morse and Steven Hawkings. Juggling the two problems, he finds the gracious help of Claire's dowdy roommate Hester Wallace (Winslet), who beams girl next door behind her horn-rimmed glasses. Not only does she get to play Nancy Drew, but she also gets to begin a budding relationship with her prettier roommate's old beau. It's like Danny Bonaduce leeching off of David Cassidy: it's, err, kismet. Add her majesty's secret service in the form of nosy agent Wigram (Northam) and Jericho's code breaking coworkers, and you have a full house of English gents and ladies playing spy games far over their heads. Wigram gives the film its best scenes, probably because Stoppard had never written a character like this and was, therefore, more willing to play with writing choices he had long before exhausted on other characters. Northam, too, is due some attention for the work: it is further proof of his acting abilities, which have been seen in great use on films like An Ideal Husband, The Winslow Boy, and Gosford Park. His scenes are rare, though, but the sharp writing by

Stoppard and the nimble direction by Apted and editing by Rick Shaine help keep the film

going when Wigram is not around. Despite the fact that their lead character is rather

uninteresting, at least in the form Scott plays him, Enigma still comes out as a

nice, simple achievement. Its historical interests are often interesting (the fact that it

correctly thanks the Polish military for the Enigma machine is enough for some

recognition) and its production values are first rate. Unfortunately, Enigma is a

British production that will probably only play in smaller venues or art cinemas without

getting much attention around the rest of Middle America. Enigma will come and

go, and most people will continue to think America was completely to thank for the

decoding of Enigma as they watch U-571 again on HBO. |