Director: Starring:

OTHER REVIEWS: |

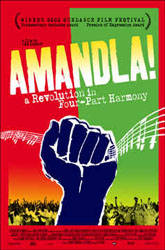

Amandla! A Revolution in

Four-Part Harmony BY: DAVID PERRY If the American dependence on slavery and the ensuing Civil War had taken place at the end of the 20th century instead of the 19th, it might have looked something like what happened in South Africa. The apartheid, which effectively made Africans second-class citizens in thier native lands, was seen as a travesty for most people around the world -- part of the reason that Nelson Mandela was finally released and allowed to peacefully become the elected president of South Africa was the push of Western nations for the Boers to catch up. Another reason that there might be some correlation between two of the darkest periods in interracial relations between those of European heritage and those of African heritage is the use of music for the downtrodden. As the whites were allowed to enjoy the wealth of free labor and free land, the blacks found their own mode of protest through songs that exalted their hope for a better future. Amandla! A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony looks at the peaceful protests that came about during the apartheid. This is not to say that the South Africans were singing of happier days -- there is the semi-anthem "Beware Verwoerd" which warns the signer of the apartheid laws that "the black man is coming" -- but the key to the peacefulness was that they came from people who had no guns. Their voices turned out to be their only real weapon, and, when the rest of the world finally came to their defense, those voices were allowed to ring beyond the slums they had been relegated to. Comparisons to the war protest songs made popular by Bob Dylan and Dion DiMucci are fitting, though the soul of the music comes more from the exclamatory worker's occasional moments of joy like "Dao" and "Long Gone (From Bowlin' Green)." It's hard to find as much happiness in one group of people in film this year as is the case with a group of two dozen singing "Beware Verwoerd" at a family reunion (it just so happens that this is the family of the song's writer). Hugh Masekela, among other notable African singers and songwriters, spends part of the film remembering the way he was exiled from South Africa because of his connections to Nelson Mandela. In most countries, they take pride in their cultural and artistic celebrities, but not in South Africa if the personality was black. Director Lee Hirsch never really brings the film beyond the constraints of television documentary filmmaking, but his product is still something of note. Much of what is shown in the film is important, not just for the views that it brings to the fore, but also the way it parallels all these moments to the history of the African rebellion. By the end of the film, it is as easy to understand why the segregated people of South Africa looked up to Nelson Mandela as it is to understand why the people attempted to hold-off violence against their white opressors. The film makes good use of the four-part harmony

structure of many of the songs and even serves as a terrific venue for the songs to reach

audiences who rarely hear works imported from South Africa. One especially forceful moment

comes when Sibongile Khumalo sings to the gods asking why her people are being treated

this way. Khumalo has the voice worthy of the Italian stage -- and, just think, her voice

would still be suppressed had just come one generation earlier. |