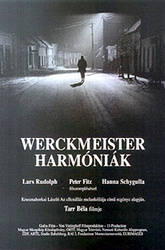

Director: Starring:

OTHER REVIEWS: The

Harmonists The

Marriage of Maria Braun The

Princess and the Warrior Sunshine |

Werckmeister Harmonies BY: DAVID PERRY [NOTE: Since this is more an analysis than a review of Werckmeister Harmonies, major plot points including the ending are given away. It is recommended that this only be read after watching the film.] The last century in Hungarian history is something that is rarely touched upon in the American history books, which stick to the idea of Germany, Austria, Italy = 'bad,' while England, France, America = 'good,' with many hints that Russia plays 'good' but was really 'bad.' However, the dynamics of Europe during the two World Wars and the Cold War that soon followed are so much more than a black and white story of 'good' and 'bad.' In Werckmeister Harmonies, the acclaimed Hungarian avant-garde filmmaker Béla Tarr looks at a nation still paying for its past, despite trying to forget it. After attempting to divide from a dual monarchy with Austria during and after World War I, the country would be attacked from all sides. To make up for their new vulnerability without the Austrian army on their side, the Hungarian government entered into alliances with Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, later declaring war on the Soviets and Americans. But they were with the Axis Powers out of need, not want, and soon tried to withdraw when Hitler began deporting Jews. The German forces then occupied the nation until the Soviets liberated Budapest. Communist rule followed, and then a new nationalism that brought democracy. Taking this into consideration and looking at the atrocities committed in the name of nationalism by Slobodan Miloševic in Serbia, Tarr and longtime partner Ágnes Hranitzky decided to use this to adapt the novel The Melancholy of Resistance by Lászlo Krasznahorkai (who has collaborated with Tarr on his previous two films Damnation and Sátántangó). It is a perfect marriage -- Eastern European environs as a backdrop to Krasznahorkai's long prose and Tarr even longer takes. The film, which was made over the course of four years with seven cinematographers, captures the weariness of a Eastern European night. The way the modern light posts shine off of homes that seem stuck in the 18th century has an evocative effect on the audience -- some directors use smoke and fog to make mystery, Tarr need only rely on his natural surroundings. This is the rare black and white film that seems impossible to ever have been in color, in equal parts because it would ruin Tarr's tableaux and because the modernity of color would seem anachronistic. Late in the film, a tank and a helicopter are used and the sensation they evoke does not come from some deus ex mechina commotion, but instead from the way these mechanical advancements have no place in the little town Tarr is filming. At the center of Werckmeister Harmonies are the many prevailing threats coming into his rustic Hungarian village. The title refers to the work of Andreas Werckmiester, who believed that God sent harmony for mankind down from the stars. A character in the film, György Eszter (Fitz), spends much of his time obsessing over Werckmiester's 12 tone octave. But soon Werckmeister is questioned -- disharmony befalls the world as people try to fill the emptiness created by time and knowledge. Not only do we learn of the mechanical problems of the city (faulty phones, electricity), but of the political discord that has taken over the villagers. At the center of the political reformation movement is Tünda Eszter (Schygulla), György's estranged wife. Using their nephew Janós (Rudolph) as an errand boy, she effectively destroys his innocence. A mailman with an interest in astrology, Janós could not care less about the platforms she and the fellow reformers are calling for -- in his wide eyes are a hope that life goes on without a hitch, forgetting any problems that might occurred in the early hours. The turning point in this town's existence comes inside a steel truck. Everyone refers to it as a circus -- one that has been known to provoke riots in other cities -- but it is actually just a stuffed whale with some odds and ends. Rumored to be in charge is The Prince (Bese), whose is only shown as a short shadow inside the truck -- an embodiment of foreign insurgence. The climax to this is, in fact, a riot, which brings the distressed of the village to march into the local hospital and destroy everything they can get their hands on, inducing memories of the varied styles and stories of Fritz Lang and Andrei Tarkovsky. The sequence ends when the rioters come upon the image of a naked and shaking old man, who carries the baggage of the past in his withering body that has seen not only his own deterioration but also the deterioration of his homeland through various regimes. With only 39 shots, little dialogue, and moments that seem to take up an entire film canister (the 39 shots comprise 145 minutes of screen time), Tarr makes far more use of metaphors than anything literal. The opening scene is an 11-minute sequence involving Janós orchestrating an explanation of the solar system of eclipses using the tavern drunks for the moon, planet, and sun -- later in the film, Tarr uses the camera in a similar fashion, first as the entity orbiting its soul, then as the soul looking out at the destruction of its orbit. For a film that is, ultimately, a figurative look at the

way politicking (both past and present) begets further travesty, it becomes all the more

ironic to consider the way the film shows some form of hope within its volatility. As the

camera pushed back from the stuffed whale lying dead and forgotten in the streets, the

viewers are reminded that its destruction came from violence and will probably further

influence violence. There is hope: the whale and its keeper (dual monarchy and the

Hapsburgs, nazism and Hitler, communism and Stalin, nationalism and Miloševic) have

been destroyed. The fear is that the vicious cycle never ends. |