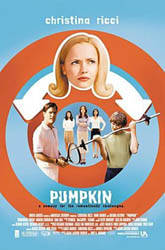

Director: Starring:

OTHER REVIEWS: Get Real Legally

Blonde Sorority

Boys Storytelling |

Pumpkin BY: DAVID PERRY In what must be the two hundredth attempt at showing Greek social community, Pumpkin arrives to kid every cliché it can find. The only problem is that it's a couple movies too late on nearly every count. The movie does succeed in pressing its point, even if the humor to the satire is nearly nonexistent during the film's first half. Carolyn McDuffy (Ricci) is the model Alpha Omega Pi at Southern California State University. She has the perk and doe eyes to invite the best girls in rush and her ability to find the beauty in everything (less a search for the silver lining and more an obliviousness to the dark clouds) that makes sorority president Julie (Coughlan) proud. Even though the house is filled with only brunettes suffering from Stepford Wives syndrome, her blonde-haired, blue-eyed naïveté serves as the perfect balance to a group of prima donnas. The rival sorority, Omega Omega Omega (a fictitious sorority to the best of my knowledge), serves as the foil to AOPi's chances at getting the Sorority of the Year Award: they are blonde and catty. The only things the two adversaries share are the bitchiness and ensemble outfits. The most telling part of their dueling interests comes in their rushing tactics: the most important part seems to be in getting a little ethnic diversity by bringing in an African American student ("she looks exactly like Whitney Huston" -- she doesn't) and a Filipino student ("She almost looks white, with those Caucasian features"). Things look pretty perfect in the SCSU street filled with sororities and fraternities, as the biggest problem seems to be in planning a formal that can knock the socks off of the alumni. But soon Carolyn finds the sadness in life when social (and Greek) mores dictate who she can fraternize with. Her life seems perfect to everyone else, especially since she has the heart of big man on campus Kent (Ball), a member of the university's best fraternity, of course. He is not the problematic love of her life, but instead serves as a cliché to try and keep her from leaving her brethren. The controversial lover happens to be a young man called Pumpkin (Harris), who is introduced to Carolyn as part of the latest AOPi philanthropy project. The uproar is not that he is so much younger that Carolyn (I'd estimate a seven year age difference), but that he is mentally and physically retarded. Pumpkin was assigned to Carolyn as her "special person" to help in preparation for a Special Olympics style event that places the local kids in direct competition with the special education kids from Orange County. The competition is almost as frightening as the condescending treatment the girls give to the kids. This riff on every satirical film in the past twenty years seems most indebted to There's Something About Mary, Harold and Maude, and Heathers, though the hit-and-miss joke structure is most reminiscent of the long forgotten But I'm a Cheerleader about another perky, popular girl learning that love is not necessarily allowed if you love the wrong type of person (in that case a girl loving a girl). The way directors Anthony Abrams and Adam Larson Broder direct is so overblown at times that it becomes hard to even attempt to believe in the statements they are trying to make. While the satirical nature of the narrative does prove to be entertaining at times (especially in what has to be among the best car crashes in recent years, only moments later eclipsed by a shot of the driver post collision), the disjointed tone to the entire film causes much of the movie to fall flat. Christina Ricci turns in one of her most surprising casting choices as well as one of her most understated performances. The actress has been known for her self-destructive and deliciously coy turns in movies like Buffalo '66 and The Opposite of Sex. Carolyn McDuffy seems to be the antithesis of Ricci's other characters, making the Stepford Sisterhood that runs her life in the film's first act seem all the more startling. Ms. Ricci seems to be finding the perfect middle line between the ditz of Reese Witherspoon in Legally Blonde (as a posh sorority girl finding the truth) and the brooding of Selma Blair in Storytelling (as a frightened girlfriend to a classmate with cerebral palsy). Her daze in the film's early moments (where she seems to be channeling Alicia Silverstone) helps to make the film's darker aspects more emotionally significant, even if the directors are still trying to juggle the tones to find the right way to treat it. Her final shot, which can only bring to mind a little Jean Seburg at the end of Breathless, is a little muted since the scenarios that brought her to the final glance is not near as weighty. Especially in the wake of Sorority Boys, which was certainly a film that supported some of the facets of Greek life, Pumpkin's berating of the world of sororities and fraternities seems more earthly than the most recent film realizations. It does give a terrifying view of the way the girls in sororities act, but at least it does not turn a derogatory eye on women by giving them the letters DOG (Delta Omicron Gamma) and making their feminist beliefs into a forgotten manifestos by the machismo finales. Pumpkin never says that it is gazing in the truth

of any situation, only commenting on the clichés that have founded them. There's no

question that Greek philanthropy is more politics than true community service, nor is

there a question whether the system is built to only help its own, but Pumpkin

never really directly tells the girls of AOPi to stop doing what has been part of its

legacy. Instead the movie seems to be saying that if Pumpkin can change Carolyn and her

lilywhite sorority life for the better, there may actually be hope for us all. |