Director: Starring:

OTHER REVIEWS: Festival

in Cannes The

Godfather The

Out-of-Towners Rosemary's

Baby |

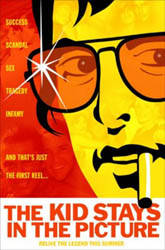

The Kid Stays in the Picture

BY: DAVID PERRY "There are three sides to every story: your side, my side, and the truth. And no one is lying. Memories shared serve each one differently." Robert Evans, the famed 1970s producer, began his 1994 autobiography with those words -- a perfect prologue to a story that involves countless subjectivities and exaggerations. The Kid Stays in the Picture takes Evans' prose (or, actually, his readings of the prose in the audio book of the autobiography) and allows the audience to get a glimpse into "the good life." He was the quintessential Angelino: rich, powerful, good looking, and tan. Evans tells his story with a great deal of self-love. Even as he recounts the collapse of everything he ever loved, the words coming from his mouth seem to be framed with a smirk. It has been 25 years since he made anything that people might consider to be a masterpiece, but who cares? Barbara De Fina and Saul Zaentz aren't half as much fun. It's no wonder that Evan's recording of the book became one of the biggest inter-celebrity gifts in years. He is a born storyteller -- a great attribute for a filmmaker -- crafting his own tale in such a way that cannot be discarded. As the story progresses, some of his memories seem to be a little illusory, but never are their completely impossible or uninteresting. This, we must remember, is the man who went from being an affluent co-owner of a women's clothing company to the big-name producer at Paramount Studios. He took Gulf+Western's pricey purchase of the No. 9 studio and turned it into No. 1. He married young ingénue Ali McGraw and lost her to Steve McQueen. He saw controversy in a drug bust and a tangential connection to a murder. Oh, and in the process he made such contemporary classics as Rosemary's Baby, Chinatown, and The Godfather. It is easy to imagine that some of these achievements would give a guy a big head, but somehow Evans has retained some fleeting level of modesty. These stories are filled with some embellishments but most of them are followed by a few admissions of painful mistakes. The divorce from McGraw is the only one dealt with in the film even though he married five times -- within his vocalizations of these moments in his life, the pain of losing someone he so dearly loved (and seemingly still does) is tingeing the statements echoing from his gruff voice. And all this occurred because he visited Los Angeles from his New York home and decided to take a dip in the pool one day. As a magazine of the time said, he "dived into a pool and emerged a movie star" when Norma Shearer asked him to play the role of her late husband Irving Thalberg in Man of a Thousand Faces. Evans is willing to admit that his acting was never any good, and those on the set of The Sun Also Rises were willing to agree: Ernest Hemingway, Tyrone Power, Ava Gardner, and Eddie Albert sent a telegram to the producer Darryl F. Zanuck in protest. The figurehead of 20th Century Fox replied, "The kid stays in the picture." It is unknown if Zanuck had seen something in the young actor, was grateful for Evans' extensive preparations, or just angry to have his decisions questioned -- all that really matters is what it told young Robert Evans: who wants to be a mediocre actor when he can instead be the kind of authority that decides who can be in a movie in the face of an author and its stars? Excuse the expression, but a producer was born. Directors Nanette Burstein and Brett Morgan choose to give the spotlight to only Evans, meaning that the opinions within are strictly from the "my side" of the historical spectrum. In many ways this seems to give the movie more life than would have been present in a talking head picture: Evans is willing to admit his own hyperbole and the rantings become all the more fascinating because of it. His is a story that has been told for decades through gossip -- it is great to get to hear it from a new point-of-view regardless of whether or not it is just as gossipy as the old. Any given year is filled with a couple hundred biographies,

most of which are made for cable television. Regardless, The Kid Stays in the Picture

rises above the masses, it remains as memorable an experience as the facts it imparts.

Robert Evans has achieved a newfound celebrity simply by giving voice to his own crazy

life. This movie might not get an Oscar in a Documentary Feature category that prefers

deep and tragic films, but it is doubtful that a little gold won't come to it soon: in the

same way his career began, Robert Evans should soon be accepting a little gift named after

Irving G. Thalberg. |